Rose Vennin

As I am shown around the Givat Haviva campus in Northern Israel, I walk past a three-meter high wooden sculpture similar to a totem pole. Curious, I ask Lydia Aisenburg, educator at the centre, whether it is indeed a totem pole and its significance. She swiftly corrects me: it is a peace tree, proudly sculpted by a group of Israeli and Arab children in one of the day-long sessions organised by the kibbutz to bring the two cultures together and further dialogue. It has symbolically stood there for a decade, persisting throughout the innumerable acts of violence in the region.

With Israel having experienced violence and instability once again this past weekend, discussing local efforts fostering harmony, such as this joint arts program, seems particularly relevant. When considering the matter, most think that peace building and international relations in general are a top-down affair, that inter-governmental agreements are those that will end conflict. However, this is only part of the story: if tension exists among the local population then even a unanimously recognised agreement at the diplomatic level is ineffective. More than ever, long-term stability in the region needs to come from local communities, with Arab and Jewish civilians working hand in hand.

This is where an organisation like Givat Haviva comes into play. Founded in 1949 as a national education centre, it is a recipient of the UNESCO Prize for Peace Education for its longstanding work in promoting Jewish-Arab dialogue and reconciliation. I meet with Yaniv Sagee, the Executive Director, who details the centre’s new strategy: striving for a shared society, the programs created aim to enhance cooperation, equality and understanding between what are today divided groups in Israel. Although this may appear to be an impossible goal in a region with a tumultuous history, Givat Haviva’s record is quite convincing at showing that change on a societal scale begins with the socio-political unit closest to the people – the community level. Projects like the implementation of common educational programs and the establishment of Arab-Jewish municipal cooperation are tiny steps in the longer stride towards regional peace, developing interaction and understanding between the two groups.

So although it may sound idealistic and trivial given the current conflictual situation, it is these tiny steps that matter today. By instituting shared values from an early stage in Arab and Jewish children’s political maturation, concrete programs like these lessen the separation between the two. As witnessed during my two-week trip to the region, hatred of the “other” is instilled from a very young age on both sides. Arab and Jewish communities can live 5 kilometres from one another, yet a world separates their views regarding the region, its history and the future they envision. Later on in the day, I visit one Jewish village, on top of a hill, and another Arab one at the bottom, both having yet to follow Givat Haviva’s program. After talking with local shop-keepers about their respective points of view, I am struck by the fact that there seems to be no interaction between the two communities – they are so close, and yet so far. In this context, how can we realistically expect the state of stability the international community repeatedly calls for?

Hence, as the peace process has slowed down to a standstill and a seemingly hopeless situation prevails, “the time to build a society of dialogue and understanding between all groups, has come, and not only at the governmental level, but even more importantly between local communities and civilians,” concludes Lydia Aisenburg. It is time to put the work of organisations like that of Givat Haviva further into the spotlight, promoting the notion of a peaceful shared society. And then only will the peace tree stand firm for centuries.

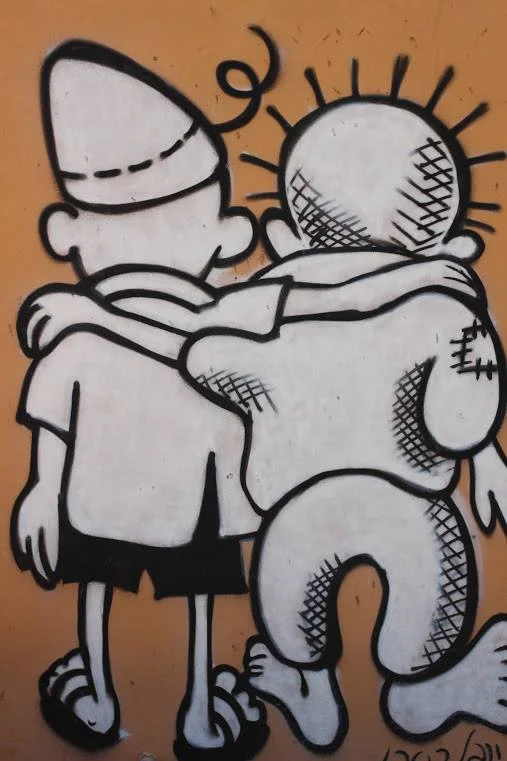

Title image taken at Givat Haviva.